Response

September 11, 2001

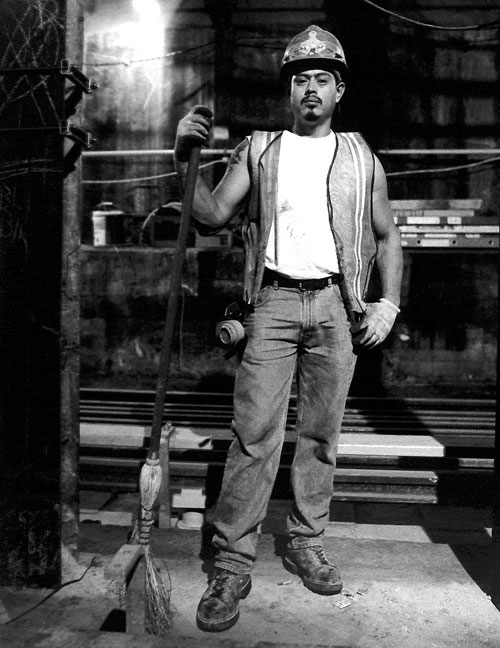

The impact of the September 11 attack in New York City was unprecedented. So too was the heroic response of MTA employees.

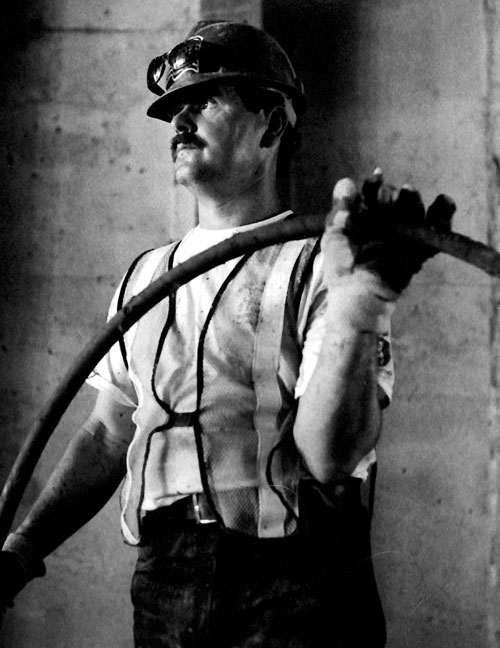

Bus drivers. Track workers. Superintendents. Electricians. Mechanics. Workers from across the transit system contributed their unique skills, equipment, and knowledge of the city’s infrastructure. They evacuated frightened citizens, transported first responders, and proved an irreplaceable resource in the process of rescue and recovery.

Their core mission, however, was to get New York moving again, as quickly—and safely—as possible. After the attack, transit professionals inspected tracks, cleared abandoned vehicles, and published daily maps as planners improvised new routes through Lower Manhattan.

All Hands on Deck

When news came of planes striking the World Trade Center, nobody was certain exactly what was happening. Like all New Yorkers, transit workers were shocked and confused. But they did know one thing: they would be needed.

Those off duty or on break hurried back to their posts. Many who were at home rushed to work, or made their way toward Ground Zero, ready to help however they could.

Caution Amid Chaos

What had happened? What was next? Were more attacks coming?

Little was known in the minutes following the first explosion on September 11, 2001. But one thing was clear. Public safety came first.

Adapting to the situation as information poured in, managers at the Subway Command Center shut down the subway system. Almost immediately, crews began inspecting Lower Manhattan tunnels for bombs, and testing tracks with empty trains. Within hours, the first few subway lines were able to resume service. By the end of the day, 65% of the system was operating.

Stop the Trains!

The Subway Command Center (now called the Rail Control Center) tracks train movements and communicates with workers in the field to keep the subways running smoothly. But at 10:20 am on September 11, they decided to shut down the system.

Damaged signals, third rail power disruptions, and water and debris in downtown tunnels severely hampered service in Lower Manhattan. But halting all subway service was primarily a safety decision. Officials were concerned about the possibility of additional attacks—and bridges and tunnels are high-profile targets.

Once it was deemed safe to resume partial service, transportation planners used their knowledge of the maze-like subway system to devise new routes that avoided the crushed and flooded tunnels under Lower Manhattan.

What Would You Do?

Imagine yourself sitting at this console on September 11, 2001.

You’re receiving reports of dangerous conditions in Lower Manhattan. You are also getting reports of stranded passengers on platforms. Do you halt subway service? Or send extra trains to aid evacuation?

Above ground, Lower Manhattan is clogged with traffic. Yet there are people desperate to leave the area—as well as first responders and rescue workers desperate to reach the area. Do you send in extra buses? Or do you try to clear the streets?

In emergencies there may be many competing options. What would you have done?

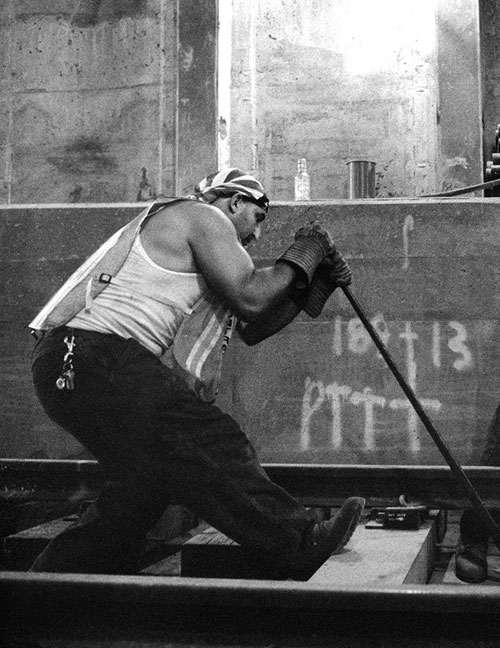

On The Front Lines

Almost immediately after the attack there were reports of dust and debris filling Lower Manhattan subway stations. Terrified passengers, crowded on smoke-filled platforms, were relieved as subway operators made final stops in Lower Manhattan and carried them to safety.

With subway service disrupted, New York City Transit rerouted buses to aid evacuation. Metro-North and LIRR dispatchers put all available trains into service to get commuters home. And hundreds of transit workers made their way to Ground Zero to join police, firefighters, and other first responders.

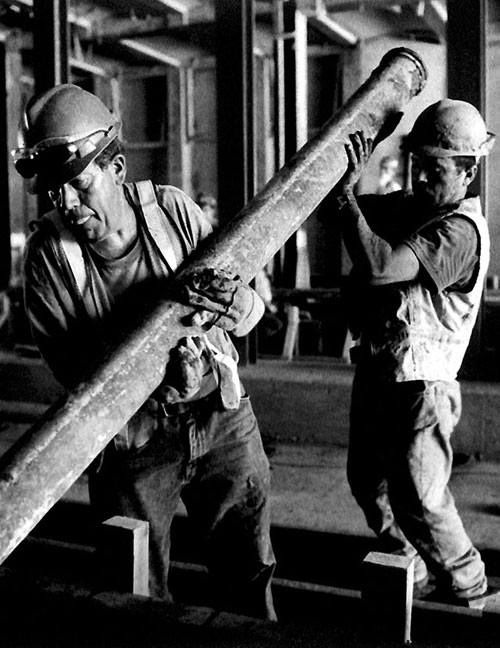

One Station’s Story: Collapse at Cortlandt

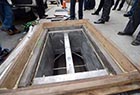

The world saw the destruction in New York’s skyline and streets. Subway workers and passengers also saw its devastating impact below ground.

The falling towers crushed the Cortlandt Street Station. Massive building beams shot like spears through seven feet of earth, through the station’s brick and concrete ceiling, and into the track bed below. John Ferrelli, Chief of Infrastructure for Subways at the time, described platform columns twisted “like a Pringles chip.” Smoke and dust filled the air.

Astonishingly, despite the unprecedented scope of the damage, no lives were lost anywhere in the subway system that day.